Holocaust survivor speaks at Valley: ‘We can not forget what happened during this period of time’

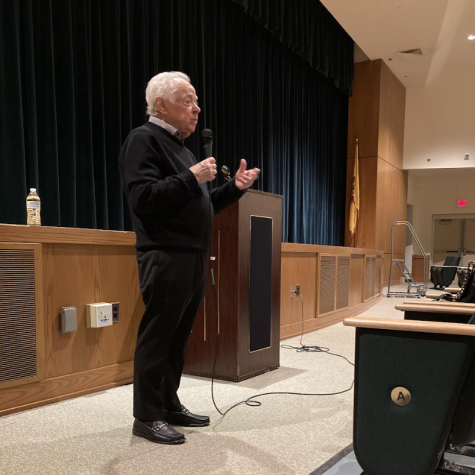

Holocaust survivor Mark Schonwetter speaks and shares his story to PV students.

Holocaust survivor Mark Schonwetter shared his story with Pascack Valley classes, Literature of the Holocaust and various history and English classes, in the auditorium Wed. April 12.

“I am sharing this [my story] with you as adult people, corporations, and university students because I feel very strongly that we can not forget what happened during this period of time,” Schonwetter said. “It is our obligation by remembering what happened to prevent anything like it from happening in the future.”

Schonwetter was accompanied by his daughter, Isabella Fisk, who says, “It has become my mission in life to become the voice of my father, and to continue to tell his story.” Schonwetter’s family stresses the importance of hearing a firsthand story of a Holocaust survivor. Fisk references PV students as “one of the last few generations of young adults” with this privilege.

Schonwetter and his family had lived in Brzostek, Poland for years, but they were forced into hiding when Germany invaded in 1939. He recalls seeing many soldiers and planes flying over his village as a little boy, even confusing the foreign planes for birds. He shared how the Gestapo, the Nazi police force, forced all Jews to wear an arm belt with the Jewish symbol the Star of David to mark them, systematically barring Jewish kids from attending school.

Schonwetter and his family were then told they had 24 hours to find a new home because the Gestapo was taking their farm. That same day, Mark’s father, a leader of the local Jewish community, went missing. Mark and his sister found refuge in their friend’s house and stayed in their kids’ rooms, while their mother stayed at his cousin’s house.

Soon after, the Gestapo came to search the house Mark and his sister were staying in. They were told the Schonwetters were there, but their friend did not say anything. The police then asked his kids how many siblings they had, attempting to expose Mark and his sister. However, she quickly responded that she had 8 siblings, accounting for Mark and his sister.

“I was the luckiest kid in the world at this moment that she was smart enough to include me in the count of her brothers and sisters because if not, I wouldn’t be standing here today talking to you,” Schonwetter said.

After this encounter, their host and friend advised the Schonwetters to go to a ghetto where many other Jewish people were staying. Mark, his sister, and his mother walked 50 miles and were able to secure a tiny house on a stepladder. Schonwetter recalls the bad conditions of the ghetto and experiencing strong hunger. With no shower, no change of clothes, little food, and illness all around, Schonwetter was grateful he made it out alive.

“We were lucky that we survived because you didn’t have a doctor to go to give [us] medicine because there was no medicine since there were no drug stores,” Schonwetter said. “We saw a lot of people dying. You just hope there’s some way you can live.”

Willing to do whatever it takes to get out, Schonwetter escaped the ghetto by tying a blanket to a barbed wire fence and getting thrown over. After this, they lived in the forest, struggling to find edible food. As the winter arrived, the Schonwetters searched villages at night to find farmers willing to take them in. He recalled his mother having him sit and wait outside while she asked. If no one took them in, they slept under trees on the outskirts of town, even on top of the snow.

“So you can imagine how pleasant this was,” Schonwetter said with a laugh. “It was tough.”

Schonwetter explained his mother’s smart choices, including when his family came across a larger group of Jews also hiding in the forest, she decided to stay separate, to be able to move faster and be less noticeable. Inevitably, this choice saved their lives.

“About a week later, we heard machine gun shots,” Schonwetter said, “Then we decided to go back to where the shots came from. So when we got to the place what did we see? Bodies. Everybody was killed.”

When winter came, there was no way for them to continue to survive in the forest, and they luckily found a farmer that was willing to help. The farmer dug a hole for them in his pigsty where the Schonwetters lived for three months, laid down under blankets. He described it as tight and uncomfortable, with only enough space for them to lie down.

Schonwetter described that he and his sister complained about the living situation, particularly the smell. However, his mother would always reassure them and explain that they were lucky to have food, and not to have to sleep in the snow.

Schonwetter’s mother always said, “look positive.”

When the summer came, they were forced to leave when the German front lines moved up. Schonwetter’s mother decided to follow other groups of farmers as they escaped to find a new place to hide.

“That shows you again, how my mom was thinking,” Schonwetter said. “How she was always thinking of every little thing trying to find a way to survive with the two little kids.”

As they moved into the villages, Schonwetter’s mother gave them new names and told them that they would have to learn Christian prayers and practices to blend in so that people would be willing to help them.

“She was explaining to us in case a farmer will take us and we live in their house,” Schonwetter said. “Polish people are Christians. They pray before they eat, so we have to pray with them. They go to church, we go with them.”

After five years in hiding, the Schonwetters learned that the Germans had lost the war.

The Schonwetters remained quiet in the forest to make sure they were safe before leaving for a larger village to start their new life.

“‘We are the soldiers of the Soviet Union.’” Schonwetter remembers the soldiers saying, “‘We liberated this village for you. The war is over.’”

English teacher Valerie Santo brought in Schonwetter for the Literature of the Holocaust Class, who have been reading Schonwetter’s memoirs in the book “Together: A Journey for Survival” written by his daughter, Ann S. Arnold.

“I think it’s so important for our students here, particularly in the Literature of the Holocaust class and the other students here to really see and meet someone who has experienced this firsthand,” Santo said. “There are so few survivors.”

Schonwetter has been coming to speak at our school for years, but this is the first time since the pandemic that he has come to speak to PV students, now speaking to a completely new student body.

“Soon everyone who was involved will be someone who has passed and just a name in a book,” Santo said. “It’s so important to meet living, breathing people to share their stories because I just feel like there’s so much more compelling to hear people speak firsthand.”

Schonwetter ended his story by stressing the importance of love over hate.

“We have to strongly believe and teach each other that we are all human,” Schonwetter said. “Does it make any difference if we are Christians, Muslims, or Hindus? Within any other religion, we are just human beings.”

Sophie Kolax is a senior and the Managing Editor at the Valley Echo. Her article "PV sophomore cast in movie" was published in the Pascack Press in 2020...

Maya Schlessinger, Pascack Valley senior, is an avid writer of all things PV. Joining the Valley Echo sophomore year, she learned quickly and rose in the...