From The Smoke Signal to The New Yorker: ‘He turned out to be a really terrific editor’

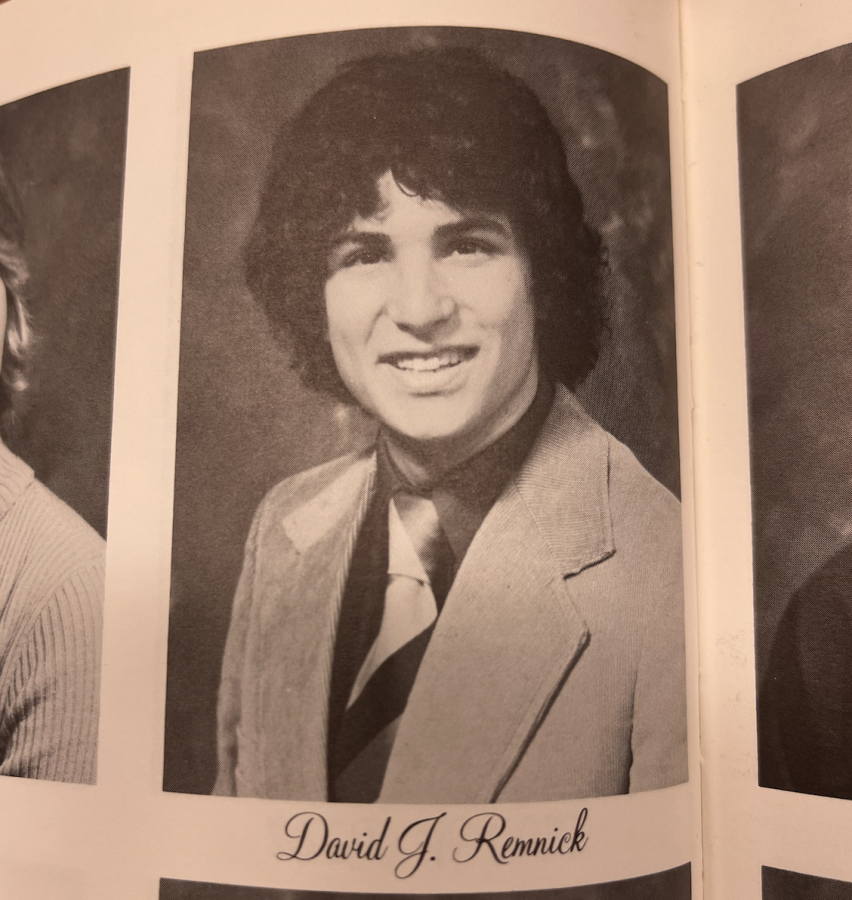

David Remnick in his senior year yearbook photo at Pascack Valley High School.

Winning a Pulitzer Prizes and writing 13 books, David Remnick has been in the role of Editor-in-Chief for The New Yorker for several years. However, his first and only experience editing articles before joining The New Yorker was during his time with Pascack Valley High School’s The Smoke Signal, now named The Valley Echo.

Remnick is a member of PVHS’s class of 1976, graduating with the ambition of becoming a writer.

Lois Jasper, former Pascack Valley and Pascack Hills teacher and Remnick’s class advisor while he was president of his grade’s student council, remembers Remnick as having great values and determination. One specific moment that she recalls was when Remnick and a few other kids went to the Board of Education with a complaint they had—despite Remnick’s father being on the board.

Jasper recalls a conversation with Remnick when he said, “‘That’s what you have to do when something bothers you, you have to be organized, you have to be polite, and you have to speak out,’ that just blew me away.”

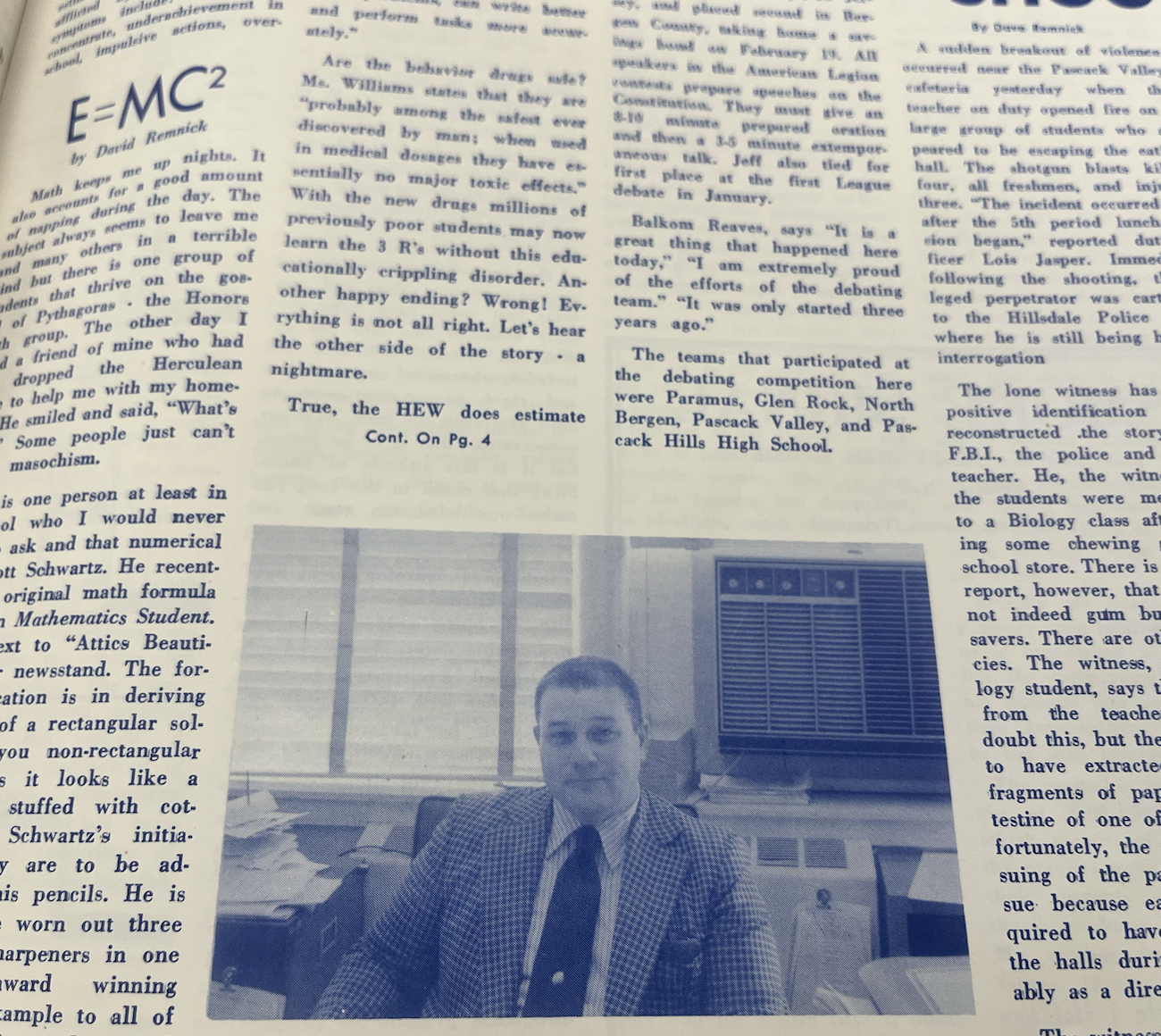

During his time at PV, Remnick was very active in the community. PV history teacher Jeff Jasper remembers creating a sports newspaper with Remnick. In addition, Remnick recalls being primarily one of the only writers involved in The Smoke Signal. While Remnick can’t recall a specific time frame during which years he was involved in the newspaper, he remembers that it was not a very popular activity at the time.

Remnick explained that the process he encountered working on The Smoke Signal was very different compared to what journalists are used to doing today. Remnick said that during his time in high school, there were no computers, so the task of creating newspapers by hand was left to him.

“You’d write these stories, then you’d have to print it up in columns, and then take a razor knife [to] cut the columns,” Remnick said. “And so I was doing an arts and crafts project as well as journalism. I would do this by myself at home, on the kitchen table.”

Since Remnick was primarily writing and creating the newspaper by himself, he resorted to creative ways to make the staff look larger than it was.

“I had to make up fake names for some of the articles,” Remnick said. “I couldn’t write David Remnick all the time. So I [would] write Joe Smith or Sheila Smith.”

Remnick recalls that the articles he wrote were mainly features, news, and sports.

“I’m ashamed to tell you [what we wrote about] because I think the idea of student journalism is to make a little trouble,” Remnick said. “It is to question authority and learn how to report, and I don’t really [think we got] into terrible trouble.”

Upon graduating from PV, Remnick already had a strong idea of what he wanted to do as he left for college at Princeton University.

“I knew exactly what I wanted to do,” Remnick said. “I want to be a writer and a journalist. And I wanted to be that from the time I was really young.”

Remnick majored in Comparative Literature, “which is basically like a fancy [way] of saying English,” according to Remnick. He also studied Russian and French during his time in college and said that this education was helpful later in his career.

“I was lucky here and there to run into a teacher that [was] strong in English: it was inspiring and I took an interest in that,” Remnick said. “So at Princeton, which is strong [in] everything, the world was my oyster. The academics at Princeton [are] what I really loved.”

In college, he didn’t work for The Daily Princetonian, the newspaper on campus; however, he found other ways to get involved with newspaper publications and earned money from doing so.

“I needed to make money, and I worked as a stringer,” Remnick said. “I didn’t work as an employee, but if [a local newspaper] needed a story, I would cover it for 50 or 25 dollars.”

Remnick said that although he chose not to work at The Daily Princetonian in order to earn money, he did miss out on the experience of working with 50 other people.

During his senior year at Princeton, Remnick had another newspaper opportunity: an internship with The Washington Post. He expected to be able to work there after college; however, according to Remnick, because of the merger between The Washington Star and The Washington Post, the newspaper said, “We’re gonna hire the best people that have 1,000 times more experience [than] you” and to “get lost for a year and just go away.”

After college, Remnick went to Asia to teach English for a year. He worked at The Washington Post as a sports writer, a culture writer, and a foreign correspondent in Moscow, where he said his knowledge of Russian came in handy.

After ten years at The Washington Post and a stint of time during which Remnick wrote a book titled Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet, Remnick had coffee with Tina Brown, then Editor-in-Chief of The New Yorker. That conversation landed him a job offer as a staff writer for The New Yorker.

Committee Attempts Reform. (Sarah Shapiro)

“[I] was editor of the magazine, and I thought [Remnick] was an outstanding writer and actually got him the job as a staff writer,” Brown said. “I met him and asked if he would like to join us as a staff writer because I had just taken over the magazine, and I was looking to restart the talent at the magazine, and he was obviously a wonderfully talented, vivid writer.”

Brown said that not long after he started at The New Yorker, Remnick started to be the person people would turn to for a second opinion or assistance.

“[Remnick was someone] who I could always ask ‘Do you think I should publish this? What are your thoughts about it?’” Brown said. “[He was] somebody who I knew that I could turn to. One of the things that was so great about David is he has a remarkable ability to write under pressure and with speed.”

Brown remembers a time when the staff used to count up the number of articles each person had written. Remnick outperformed and produced more than the other writers.

“He just has this [ability] to sit down without any sort [of distractions], unlike most of us, and to be able to just crank out something that’s so above standard; it’s remarkable,” Brown said.

Brown thought that when she left it seemed obvious to her that Remnick was one of the first people the owner would look at when naming a successor.

Then, on one random Monday, Remnick said was offered the role of Editor-in-chief and given an hour to decide.

“He turned out to be a really terrific editor, as well as writer and manager of [the newspaper],” Brown said. “Him staying there as long as he has [is] quite remarkable, and, at the same time, he’s also diversified a lot of what the magazine does: starting podcasts and doing books. [He] has kept the magazine in the top field.”

Remnick shared that his role as Editor-in-Chief isn’t just about editing his staff’s work but is also about caring about his staff and treating them like human beings, empathetically.

“There are issues that have to do with human beings who have ups and downs in their lives, in their personal lives and their creative lives,” Remnick said. “I don’t want to just be an effective editor. I want to be a decent one as a human being, and that takes attention.”

After 25 years as the Editor-in-Chief of The New Yorker, Remnick chuckled when remembering where his only experience editing came from: The Smoke Signal.

Sarah Shapiro is a senior who has been in The Valley Echo since her freshman year. She became an editor in her junior year and editor-in-chief in her...