PV community recounts Armenian history

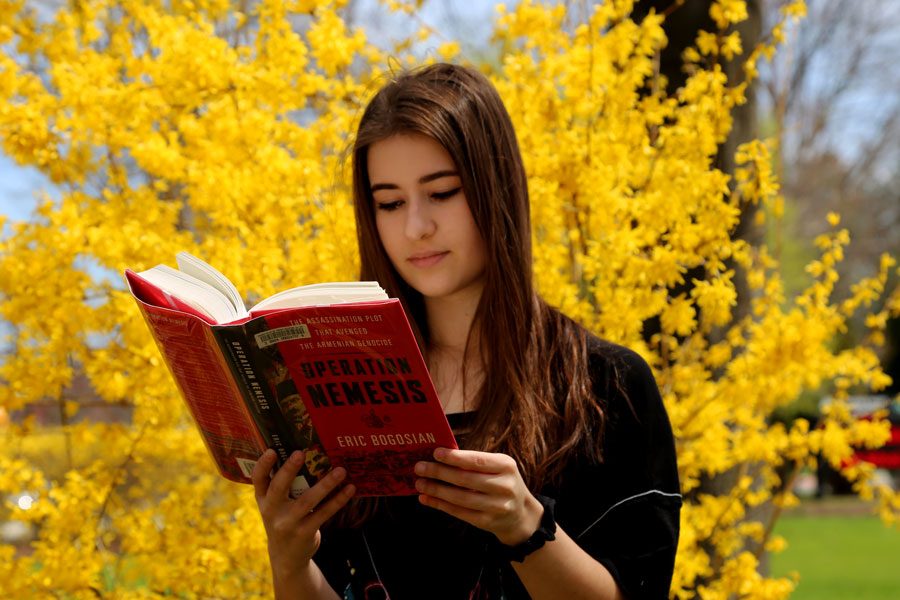

Sevan Gulleyan reads a book about the Armenian Genocide. Students and faculty tell their stories of their ancestors who fled Armenia in 1915, making this the 103rd anniversary.

In 1915, Turkish Government leaders set a plan into motion that would forcibly remove and massacre the 2 million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. By the end, 1.5 million people were killed. This is regarded by most historians as a genocide—a premeditated and systematic campaign to exterminate an entire population. However, the Turkish government does not acknowledge that these events happened and it is still illegal in Turkey to talk about what happened to Armenians during this time.

Yesterday, April 24, marked the 103rd anniversary of the genocide. These are the stories of relatives of Pascack Valley students and faculty who continue to tell their family’s story of the Armenian genocide.

Ken Sarajian

During the Armenian Genocide, Ken Sarajian’s great-great-grandfather on his mother’s side —a priest— was sentenced to death by the Turks during the massacres in the 1890s. He was able to get away through intervention by the church.

His great great grandfather arrived in Constantinople on April 24, 1915, also known as Red Sunday, which was the the day that the Turks sent intellectuals and political leaders to labor camps by train. This was intended to deprive the Armenian population of leadership and a chance for resistance. To document who had been taken, they inscribed the names on prayer beads which can be seen in The Armenian Genocide Museum Institute in Armenia.

Sarajian’s great great grandfather later died in a death march. His son then became part of the resistance and fought for the liberation of Armenia.

On his father’s side, Sarajian’s grandfather had been conscripted into the Turkish army. He escaped to America, leaving behind his parents, wife, and unborn child.

For 60 years, there was a picture hung in his grandfather’s house. His grandfather told everyone it was his sister and her child, but after he died, his grandmother told Sarajian’s family that it was a picture of his wife and child that he had never seen. They were killed as he was trying to bring them to the United States which traumatized him for the rest of his life.

The woman Sarajian’s grandfather married was also Armenian, who, before escaping and coming to America with her brother, had been taken with her sister though the desert by a Turkish family to serve as slaves. Before his grandmother’s sister had been taken, she drowned her children in a lake rather than have them suffer in a death march.

“It is important to continue to remember these events because it was the blueprint for the holocaust and has shaped the geopolitical world of today,” Sarajian said. “Turkey does not acknowledge the genocide and do not give Armenians equal rights. Armenia is blockaded by Turkey which means it can’t grow and the fighting continues even today.”

Lara Assadorian

Between 1894 and 1896, Turkish military officials, soldiers, and ordinary men sacked Armenian villages and cities and massacred the population, killing hundreds of thousands of Armenians. As a result, PV junior Lara Assadorian’s father’s grandparents fled Armenia from the danger they were in and because of the brutality that had already taken place before 1915.

Like many other Armenians facing persecution during this time, they fled to Tanta, Egypt, while others fled to countries in the Middle East and the United States. After arriving in Egypt, they faced many hardships, starting their lives over in order to create a better future for their children.

“To me, it is important for it [the Armenian Genocide] to be remembered because it has always been a part of my life, “ Assadorian said. “It is very important for people to be educated about this genocide because people rarely talk about it, leading it to be called the ‘Forgotten Genocide.’

The Tavitians

The Tavitians’ mother’s side of the family was in the region Kars and their father’s side was from Sassoun and Kilis. Their mother’s family had to run twice, the first time in 1915 and the second in 1918. In 1915, they had connections in the government and were told to leave town because it was not safe and that they would be alerted when it was secure to come back.

In 1917, when the were told it was safe, they returned. However, there was another attempt to kill the Armenians in 1918, so they fled in the middle of the night. The family left everything behind, including their valuables and soap factory, fleeing to Ga.

Her father’s family were also alerted the night before an attack and walked 400 miles to Aleppo in Syria. Both families lost friends and family, leaving their hometowns, the places they grew up in, and left their lives behind.

“It is important we continue to remember the Armenian Genocide today because it is a big part of our history,” PV freshman Albertina Tavitian said. “We need everyone to hear our stories and how our ancestors were tortured and killed, yet somehow, some of them survived. Like what the movie ‘The Promise’ says, ‘our revenge is our survival.’”

Leana Hacopian

PV senior Leana Hacopian’s family was living in Armenia during the genocide. This family consisted of her great-great-grandfather from her mother’s side, his younger sister, and his parents. The genocide completely removed her family from Armenia.

When Hacopian’s great-great-grandfather and his family were trying to escape Armenia, their only option was to escape through the mountains away from danger. While escaping, her great-great-grandfather watched his parents die due to the extreme conditions they were exposed to.

After a few days and nights of persevering and walking through the mountains, he woke up one morning and couldn’t find his sister. Despite this, he had to continue, knowing that his life was on the line.

He ended up in the Middle East where he attempted to build a better life for himself. He found his wife, started a family, and received a job to support this family.

Many, many years later, her great-great-grandfather received a letter that was sent from his younger sister. This letter mentioned that she had been sold to an Arab man to become his bride and now had many children to take care of. Unfortunately, they never met again.

“Because of the genocide, Armenians are scattered all over the world. My family wouldn’t be here in America today if it weren’t for the genocide,” Hacopian said. “We as Armenians and those who support Armenians want to remember the genocide so we can try as a community to stop a tragedy like this from ever happening again.”

Knar Alashaian

PV junior Knar Alashaian’s mom’s side of the family was not involved in the genocide while her dad’s family was in the city of Dikranagerd and the village of Malatia-Sebastia. Her great grandma’s (her grandma’s mom) family knew a Turkish diplomat, so when news came out about what was happening, her family sent her to get the diplomat so that they would be protected.

It turned out that the diplomat was not there, so when her great-grandmother began to return, she saw the Turks at the gates of the city. She concluded that her family was gone so she did not continue.

A Turkish family took her and she became a servant for the family. As a servant, the daughter of the family hated it, so she would hit her and treat her poorly. Then, Alashaian’s great grandma left and lived in orphanages.

Alashaian’s great-grandfather left after he heard about the genocide beginning starting.

Although her great grandma was a survivor, she was too young to remember all of the little details.

“You remember the genocide to honor your ancestors that have passed away so that it doesn’t repeat itself, although it continues to,” Alashaian said.

Sevan Gulleyan

Prior to the genocide, my great-grandfather on his dad’s side was a businessman in his village and worked with his father. My great grandmother was 16 years old in 1915 and then married my great-grandfather. Their honeymoon was shortened since both families had to flee.

My great grandmother hid her jewelry in her clothes and used golden coins as buttons to decorate my great grandfather’s winter coat. My great grandfather hid the rest of the family jewelry under a tree since it was too dangerous to take it with them. All the hidden pieces of jewelry were found and stolen by the Turks.

On a road in the desert road, great grandmother’s sister was shot by the Turks where she later died. My great grandmother’s brother, who was newborn at the time, was left to die behind a rock since his mother ran out of food and milk. His father, when he found out what his wife had done, went and rescued the boy who lived until 101 years old.

Their journey took them to Jerusalem, where after living there for six months as refugees, they continued their journey and settled in Zahle, Lebanon.

My great-grandfather and great grandmother were married at 20 and were from the same village, Evereg, now modern-day Develi, Turkey. As a result of the genocide, they were driven out of their homeland and settled in Haifa, Israel. Later on, they moved to Beirut, Lebanon.